Recently, there have been conversations on social media regarding the 4Ps of marketing. Clearly, there are strong, enduring, and divergent ‘opinions’ on this topic. With this in mind it would be prudent [not to mention brave] to share an abbreviated summary of the academic literature regarding the marketing mix and the 4Ps.

The marketing mix & the 4Ps

The strategies and tactics within a marketing plan and the marketing action plans are often referred to as the marketing mix. Moreover, the marketing mix is also employed after the marketing planning stage to implement tactics, evaluate the outcomes, and take corrective actions to achieve the short-term and long-term objectives of the organisation. Given the importance and past attention given to this topic it seems prudent to provide a brief overview of the marketing mix.

In 1953, Neil Borden, the President of the American Marketing Association, presented the concept of the marketing mix, he acknowledged the work of a colleague, James Culliton, who employed a recipe metaphor to describe marketing practitioners as ‘mixers of ingredients’. Then, Borden (1964) updated his earlier work (Borden, 1942 & 1953) reinforcing the 12 elements and 4 market forces as the marketing mix.

In his gentle manner, Borden (1964) states the importance of advertising and emphasises that it is one element of the marketing mix and, therefore, advertising tactics must work in concert with the overall marketing strategy.

“

An able manager does not ask, “Shall we use or not use advertising,” without consideration of the product and of other management procedures to be employed. Rather the question is always one of finding a management formula giving advertising its due place in the combination of manufacturing methods, product form, pricing, promotion and selling methods, and distribution methods (Borden, 1964, p.8).

Borden also identifies that branding, personal selling, advertising and promotion are distinct activities. This is a notable event in the evolution of marketing as it distinguishes, from an academic perspective, the marketing concept from the selling concept.

The marketing mix are like the ingredients in a cake mix. When the cake is baked, it is hard to distinguish one ingredient from another – unless the ingredient has been overlooked and is missing.

McCarthy (1960) conscious of Borden’s list of 12 controllable marketing mix elements and 4 market forces summarised the marketing mix concept into the 4P format [Product, Price, Place, Promotion]; his aim was to provide a mnemonic for the students in his basic marketing class.

Unfortunate consequences

Over the last 50 years the 4Ps of marketing has received a great deal of attention. Let’s be clear on this – the 4P framework has an important place in the evolution of marketing theory and should be appropriately acknowledged. However, there are 2 unfortunate consequences that should be highlighted:

- McCarthy’s ‘4P mnemonic’ is often referred to as the ‘marketing mix’, which diverts attention and oversimplifies Borden’s major contribution to marketing (Quelch & Jocz, 2008)

- McCarthy’s original textbook provides a more comprehensive generalised discussion of marketing than just the 4Ps. Including where he describes marketing as ‘to best satisfy consumers and accomplish the firm’s objectives’ – an insight that is often overlooked and rarely acknowledged

The widespread adoption of the 4Ps by marketing lecturers demonstrates its value as a mnemonic over many years (Cowell, 1984). Social media posts promoting the 4Ps still receive favourable responses – with some remembering the 4Ps with a sense of attachment and nostalgia of their university days and some resort to personal attacks on those who question the rigor and validity of the framework.

Marketing theories may have a life cycle

However, as marketing and society evolved the 4Ps appears to have travelled through a life cycle [introduction, growth, maturity, and decline]. Some scholars suggest that with time, the 4Ps no longer reflected marketing principles and practices (van Waterschoot & Van den Bulte, 1992). Gronroos (1994) and Yudelson (1999) suggested that a 4P framework for marketing textbooks was a mandatory/acceptable structure dictated by publishers and a convenient structure for textbook authors.

Gronroos (1993) suggests that the 4P framework has confused many readers, particularly those new to marketing. Gabbott, (2004) stated that it was hard to defend a model that is no longer practiced. Sweeney (2007, p.97) agreed and suggested that it was a “relic of the past.” Ettenson, et al. (2013) state that it is now rare to hear a marketing practitioner refer to the 4Ps. Osborne and Ballantine (2012) stated that the 4P is organisational-centric and blind to the dynamics and relationships within a market. Some textbook authors present the 4P framework with cautionary warnings (for example – Jain, Haley, Voola, & Wickham, 2012; and Kotler & Armstrong, 2014).

Other scholars have call for modifications, for example:

- Lautenborn (1990) suggested replacing the organisation centric 4Ps with customer centric 4Cs [customer needs and wants, consumption costs, convenience, and communication].

- Peppers and Rogers (1997) proposed replacing the 4Ps with 5Is [identification, individualisation, interaction, integration, and integrity].

- Sheth and Sisodia (2011) suggested the 4As [acceptability, affordability, accessibility and awareness].

- Ettenson, Conrado, & Knowles (2013) proposed modifying the 4P framework with the acronym SAVE; as this is more suitable in B2B marketing situations and is more customer centric, iterative, and service orientated. They suggest marketing practitioners should consider product as SOLUTION, place as ACCESS, price as VALUE, and promotion as EDUCATION.

- Pride, Ferrell, Lukas, Schembri, and Nuninen (2015) carry on the practice of adding more Ps and propose there are now 8 Ps – product, price, promotion, distribution [place], people, physical evidence, processes, and partnerships

- Festa, Cuoma, Metallo, Festa (2016) suggested replacing the 4Ps with the 4Es [expertise, evaluation, education, and experience] of wine marketing.

There are many areas of marketing that are no longer accommodated by the 4Ps. For example, place represents where the product meets the customer. This may makes sense for fast moving consumer goods [FMCG] and the retail focus of marketing in the 1950s and 1960s, however, a limited perspective in a number of marketing genres (Edgar, Huhman, & Millar, 2015). Cognizant of the gap, many 4P marketing textbook authors expanded place to include product distribution, however, this notion of place as distribution is misleading – because the distribution of products [material or non-material] is a service [logistics see Borden]. Furthermore, place can be the dominant component of the product – [as in the genre of tourism marketing].

Confusion between strategies and tactics

Interestingly, other scholars highlight the 4P confusion between strategy and tactics. Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliott (2012) suggest that the term ‘promotion’ is most often used incorrectly. Correctly used, promotion implies a short-term tactical tool. However, McCarthy’s use of promotion implies a holistic, long-term, and strategic meaning. Recognising the importance of long-term staregies and short-term tactics some scholars employ marketing communication to indicate a long-term and strategic approach and promotion to indicate a short-term and tactical approach.

The 4Ps may not be consistent across all marketing genres. For over 30 years, services marketing authors have also argued that the 4P framework is inadequate for service dominant products (Booms & Bitner, 1981; Constantinides, 2006; Lages, Simoes, Fisk & Kunz, 2013). Instead of presenting a new framework, many argued for an extended 7P framework. The 7Ps are product, price, place, promotion, processes, physical evidence and people. Others scholars have argued for additional Ps for packaging (Nickels & Jolson, 1976), for public relations (Mindak & Fine, 1981; Kotler, 1986), for partnerships (Chaffey & Smith, 2013).

Regardless of the number of Ps that are added, the format remains organisational centric – something you do to a customer, which is more in keeping with the selling concept. Whereas marketing should be seen as something you do with a customer – therefore, the question needs asking where is the customer in the 4P mnemonic?

Nevertheless, the contribution of the 4Ps to marketing is considerable and should not be dismissed as without any merit. It has helped marketing students to consider marketing as more than advertising. Perhaps, the 4Ps have retarded the progress of marketing, however, it could also be argued that the limitations have initiated a great deal of debate and through this debate the 4Ps have advanced marketing theory. Although many academics have criticised the 4Ps the concept must be considered in the keeping with the situational factors of the time.

Author’s comment:

The 4P debate is such a big topic. It is also worth warning readers that, when undertaking a review of marketing literature, divergent views on this topic may be a little confusing. This overview was provided to save readers the months that were spent researching this topic.

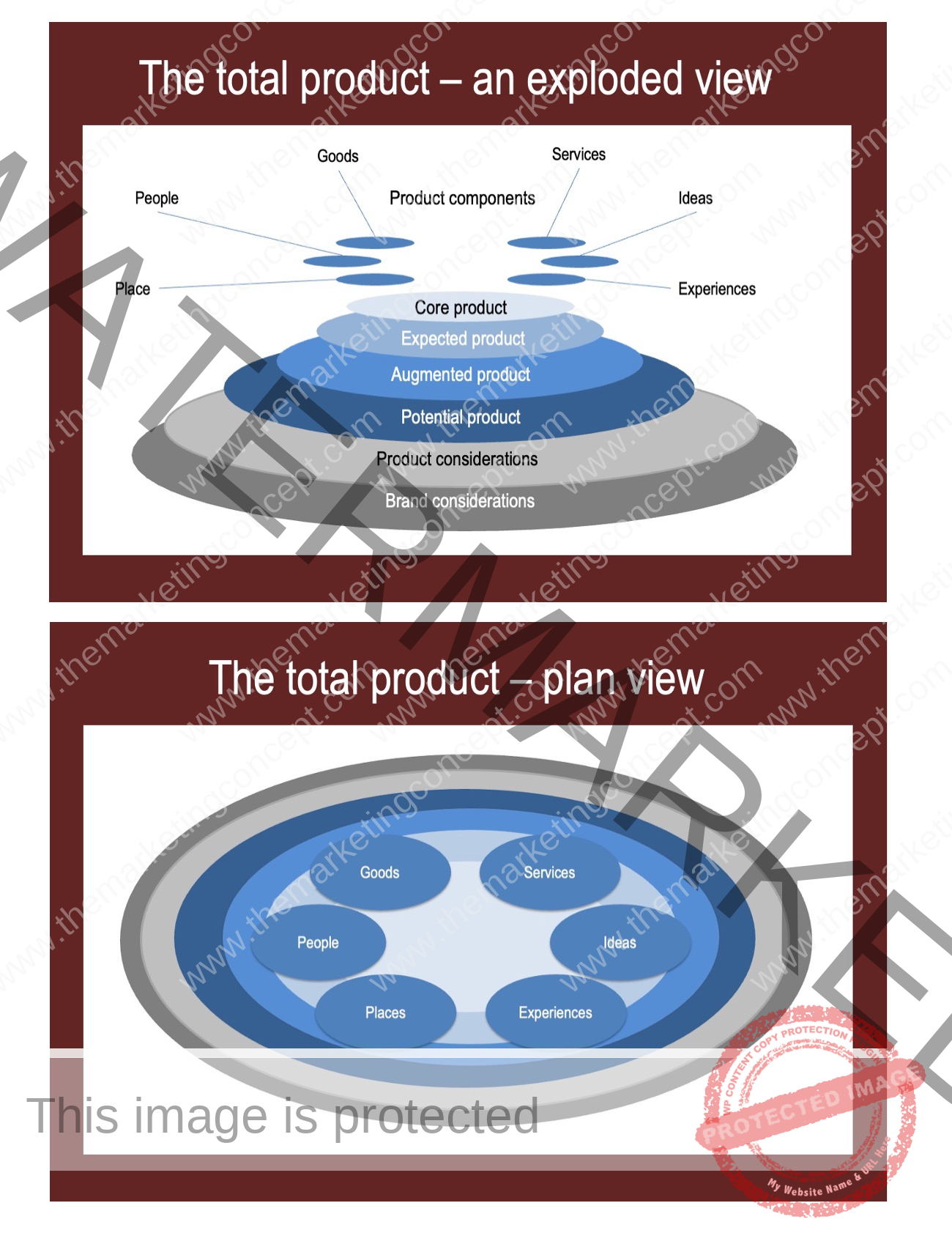

Moving forward, if we synthesise the marketing literature it is relatively simple – customers buy products – organisations market products – it is all about the unique value proposition of the total product.

Maybe there is only one P

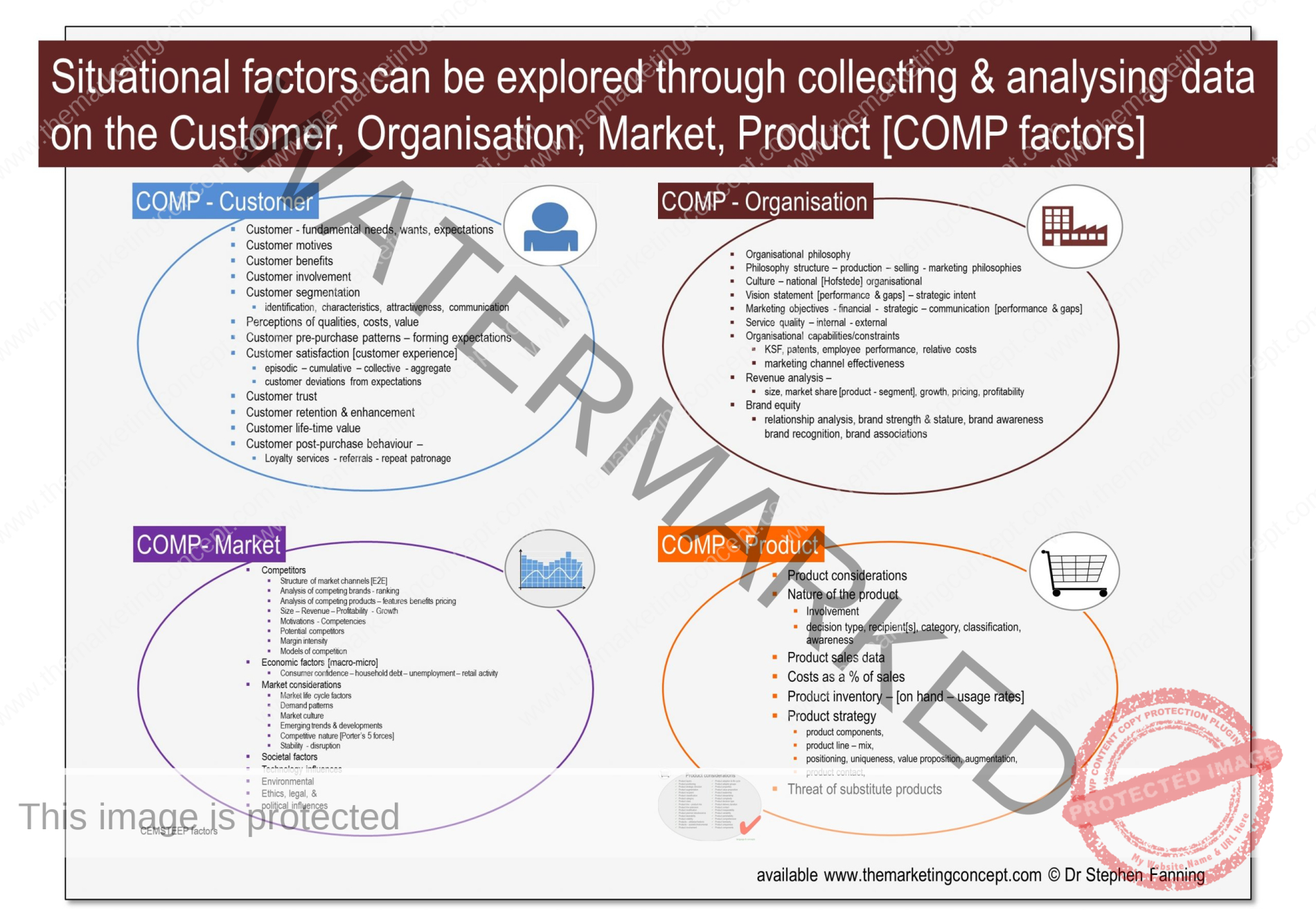

Given that the word product means the sum of all efforts – a strong argument could be made that from an organisational perspective there is only one P – Product. Furthermore, the literature suggests that each product could be explored as layers, considerations, components, and subject to the prevailing situational factors [the Customer, Organisation, Market, & Product – COMP].

expanded references are available in ‘The marketing concept: an academic perspective’